Advanced technologies are changing maintenance planning roles, and revealing the importance of good technicians and the people who manage them

By Jesse Morton, Technical Writer

According to the experts, the latest trends in maintenance planning speak to the state of the technology in the mining space. Like many other roles at the mine, maintenance planning is becoming more data driven, and emergent solutions could someday enable the job to be done remotely. As machine health monitoring data improves, certain maintenance tasks can be automated. Yet, currently some of the efforts in these directions have resulted in fewer wins than previously anticipated.

For example, according to the experts, computer scientists still generally cannot use machine health data alone to arrive at the real reason for a mechanical malfunction. Similarly, teleremote solutions have yet to prove capable of entirely relocating maintenance planning personnel to cubicles at company headquarters downtown. Both fail because they implicitly undervalue the technician who can put hands and eyes on the equipment.

The example of the teleremote LHD offers a telling comparison. The numbers it produces are promising, but by operating unmanned, a set of challenges and constraints emerge. For the moment, there has to be someone on site who knows the machine well to provide critical information on it to keep it up and running. Similarly, teleremote maintenance planning seems advantageous and in some cases could be doable, but in others causes problems that come at a cost.

Therefore, similar to how a future of robots operating alone underground remains pie in the sky for most companies, maintenance planners operating from their home office half a world away is still mostly a pipe dream. Nonetheless, the experts say, that is the way things are trending.

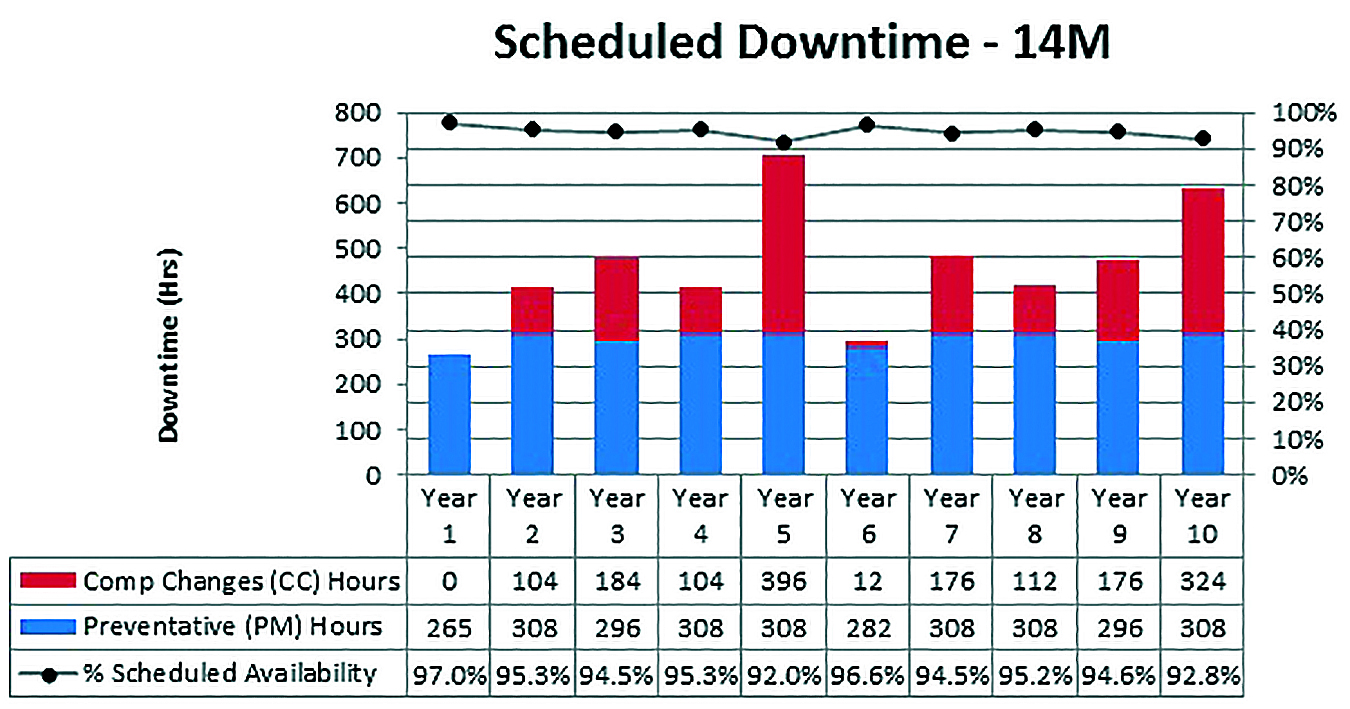

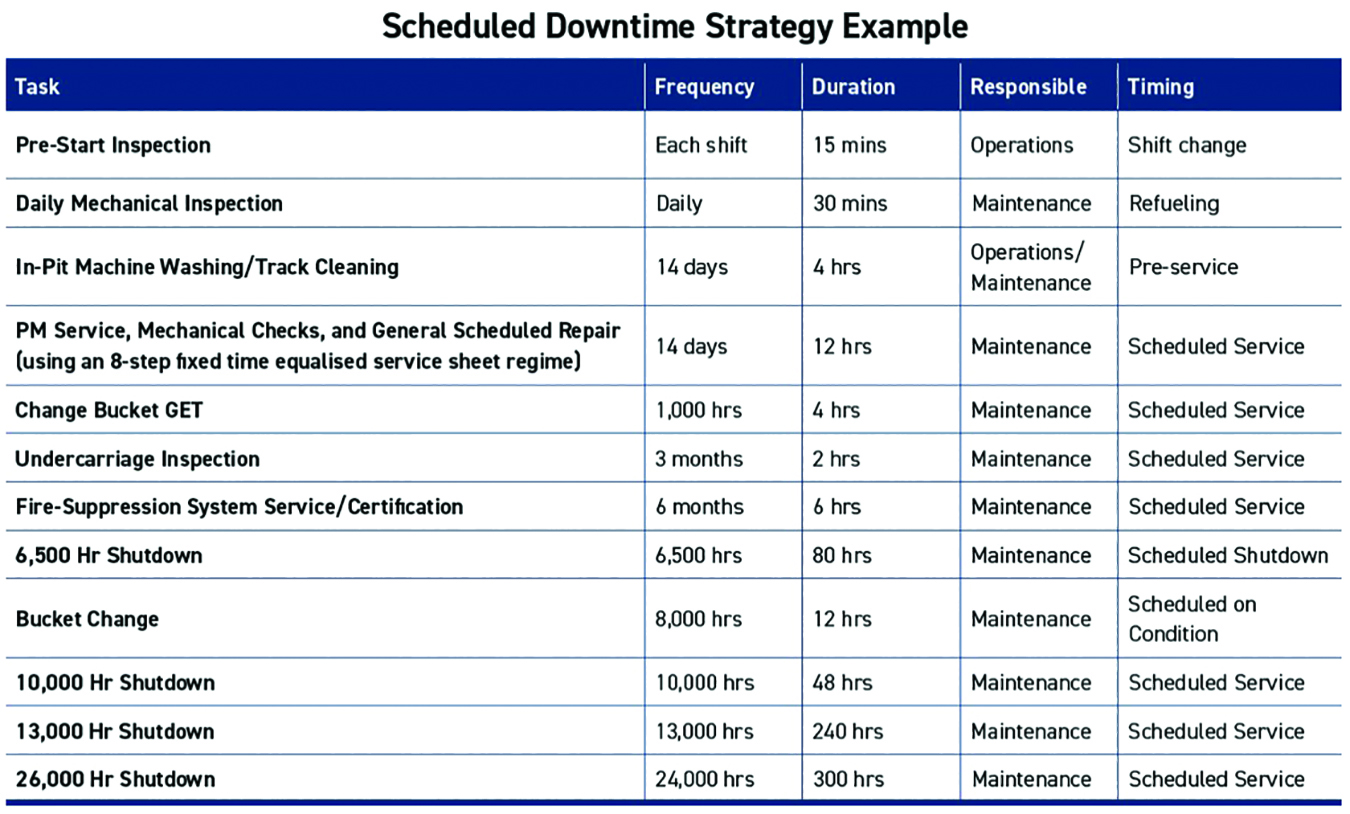

Author Gerard Wood tells E&MJ that maintenance planners should be involved in developing a scheduled downtime strategy, such as the above, as part of an asset management plan, for remotely operated equipment or for equipment that autonomously completes certain tasks. (Image: Gerard Wood)

Teleremote Maintenance Planning

Gerard Wood, managing director of Bluefield Asset Management and author of Simplifying Mining Maintenance, told E&MJ centralized remote planning is trending. “This is also true for other functions, which have been moving to centralized location far from the mine and run remotely,” he said. “It is the advances in technology that have been enabling this to occur and it is also the enabling technologies that will eventually enable planning to be done more remotely.”

Dr. Peter Knights, professor at the School of Mechanical and Mining Engineering at the University of Queensland, said advances in digital connectivity has allowed at least one major mining company to transition all maintenance planning to city-based offices.

In practice, transitioning maintenance planning to cubicles in skyscrapers is beset by challenges other companies have found to be insurmountable. “At this point in time, the efforts to make maintenance planning a remote function have not been very successful,” Wood said. “Some companies have centralized the function but then sent it back to the sites again.”

For good reason, he said. The idea of remote planning is based on the idea that maintenance plans can be forged that then work out perfectly. This premise is patently false, he said.

“The worst mistake people can make with planning is to think there is such a thing as a perfect plan,” Wood said. “We need to continually work, day in and day out, to improve the planning and make the work execution more efficient.” On the ground this looks like plans failing and then being revised, over and over again.

That reality often proves difficult to build neatly into an office schedule. “The short term, month to month, planning requires very close communication with the supervisor,” Wood said. “The number of potential problems during scheduled maintenance that can cause delays is very large and only by open communications daily or at least weekly between the planner and supervisor can the site continue to improve the planning and eliminate these problems. It is a process of continual improvement.”

Wood said he is optimistic that technological solutions will eventually enable effective remote planning. “These limitations will eventually be overcome through better communication technology and through virtual visual models of the equipment that can be updated when a machine moves past a certain point or is serviced,” he said. “Enabling the planner to see the machine and the current condition will assist greatly in the short-term planning environment.”

Standardized Data and Automation

Knights said transitioning to centralized remote planning requires a significant investment in standardizing data, such as material codes, task lists and failure codes. It would require developing a methodology to manage “standardized data, new digital skills requirements, organizational change management, and management of office and worksite communications.”

For many mine sites, the process of standardizing data pertaining to maintenance planning is well under way, and in the future, could allow for the automation of transactional-type tasks, Wood said. “For example, there is still a requirement for people to open work orders in most Computerized Maintenance Management Systems (CMMS), but this is a task that we can use AI to perform.”

Bluefield Asset Management deploys a system called Relialytics that, Wood said, “has already removed the requirement to open work orders for oil samples returning to the lab.” It automates the process of reviewing sample results, determines what action is required and files a work order in the CMMS.

“No human needs to perform the transactional tasks in the CMMS, and the data analytics is much more effective because the computer can analyze the data in an exponentially more effective manner,” Wood said. “By the end of next year, we will have done this for most forms of condition monitoring, which will significantly reduce the workload for site planners and engineers, allowing them to work on much more value-adding tasks.”

Data analytics is also being leveraged for the purposes of enhanced shift coverage and the development of proactive, planned maintenance workloads, Kings said. However, as it has been with remote maintenance planning, “the rollout of maintenance data analytics has had mixed success,” he said. “Without contextual knowledge of the site and business environment conditions, data scientists can get root causes very wrong.”

Successful analytics, Kings said, “requires a team-based approach that brings an appropriate mix of skills to the table related to the statistics and machine learning, operating context, and IT capability.”

Thus, for the moment, “with our current technologies, there is still a need to have good, and face-to-face, communications between the planner and the execution team,” Wood said.

Single Minute Maintenance

Low-tech solutions to improving maintenance events include what Wood calls the Single Minute Maintenance, which originated in manufacturing. The goal is to “incorporate lean principles into the work procedures, job design and planning” to “reduce equipment downtime and the labor hours required to execute a task,” he said.

The process involves six steps. First, itemize the tasks of the job to be analyzed. Then document each task duration. Next, identify which tasks are currently performed while the equipment is down. Identify which tasks can be completed while the equipment is still in operation. Next, identify which tasks can be reduced in duration. Finally, document new process tasks and implement required actions.

In the scheduled downtime strategy for an autonomous machine, the typical pre-start inspection would be removed. Mechanical inspection could instead occur during refueling. (Image: Gerard Wood)

Trending Mistakes

Currently, the more common maintenance planning mistakes include pushing out the service on machines to increase uptime for the immediate future, Wood said. “The companies that believe they can continually improve their equipment availability by extending service intervals and reducing the scheduled downtime continue to fail.”

Better, Wood said, is to develop what he called a scheduled downtime strategy that is part of the asset management plan. “The correct way to reduce scheduled downtime is to utilize tools for making scheduled tasks more efficient,” such as the Single Minute Maintenance method, “and not by simply pushing out the time between scheduled service,” Wood said. “By defining the needs up front, the site can deliver how much downtime the machine will require over its life and for what type of maintenance.”

Another current, common maintenance planning challenge is breaking free from the centralized-to-decentralized planning structure continuum. Wood said that when it comes to planning structure, over time many mine sites will swing like a pendulum from centralized to decentralized planning and then back again.

In a typical centralized structure, the maintenance planners answer to the maintenance superintendents, who answer to the maintenance manager. Oversight is concentrated with the superintendents.

In a decentralized structure, the high-level maintenance planners answer directly to the manager. Those planners share in the oversight with the superintendents and therefore the oversight is more widely dispersed than it is in the centralized structure.

Mine sites, Wood said, transition from one structure to the next and then return depending on performance. The state of almost constant change is due to how “both structures have problems,” he said.

Centralized planning, for example, typically has problems with communication between the planning and execution functions. “If the superintendents of those two functions don’t work together and communicate well, the manager has to step in and sort things out,” Wood said. “This often creates more work for the manager,” he said. “When planning is decentralized, you have only one superintendent to go to in order to get better performance.”

But with the decentralized model, planners often get roped into helping fix breakdowns. “They stop planning and become resources for execution,” Wood said. “In addition, decentralized planners often do things differently, causing inconsistent planning approaches across the business. When this occurs, managers want to centralize the planning function to get it in control, which introduces communication problems and removes single-point accountability.”

The Teleremote LHD Conundrum

The rise of teleremote-controlled equipment has proven to be a mixed bag for maintenance planners, the experts said. “The combination of teleremote bogging and automated tramming gives enhanced production hours as a result of reduced handover time at shift change,” Kings said. The back office cheers the increased production rate but “the absence of an operator walk-around at the start of shifts can be detrimental for machine maintenance planning, as small defects can go unnoticed.”

Wood said that without these opportunities for inspections on the equipment, it is essential that the equipment onboard data is utilized in a much more effective manner. For equipment with largely automated tasks, the asset management plan should be assessed differently than it would for entirely manually operated equipment.

“For an autonomous machine, the pre-start inspection would be removed, however, there is always a requirement to refuel the equipment, so the site may choose to continue with the daily mechanical inspection during refueling,” Wood said. “The critical thing to remember is that the scheduled downtime strategy is the essential starting point for maintaining any machine and being clear on how it will be maintained for maximum reliability and minimum cost.”

Reliability — Is It Worth It?

There has always been a point of contention in the mining industry when the budget cuts come and one of the first departments that see cost cutting is the maintenance department. This leads to the discussion around the value of reliability. We often hear of customers who place a low value on reliability because “they have swing units” or “they don’t need more tons from the mobile fleet.” But in any scenario, there is a value to be placed on availability, more specifically the reliability of the mobile fleet that translates to savings. It is ultimately the combination of the availability of the machines and supported by their reliability that makes a fleet sustainable for the mines production targets. Sometimes the less priority to good practices becomes the culture of the organization, impacting the life of the capital investments.

In 2005, Professor Peter Knights et al. put forward a model to assist maintenance managers in evaluating the benefits of maintenance improvement projects. The model considers four cost-saving dimensions, which are namely the following:

1. Reduction in the cost of unplanned repairs and maintenance;

2. Increased or accelerated production and/or sales;

3. Spares inventory reduction/optimization; and

4. Reduction in over-investment in assets and operating costs.

All of which can be achieved as a result of improving reliability. In this case, reliability is defined by the ratio of unplanned time over the total maintenance time. Mean time to repair (MTTR) and mean time before failure (MTBF) are also common metrics to measure reliability.

In order to understand the cost saving dimensions, the first principle is that there is a time saving to execute a planned task compared to the same task if it was unplanned. It can be assumed that the extra time could take “three times longer.” This means that moving any event from unplanned to planned will increase the availability. It also has impact on the cost incurred in the task which is higher than a planned activity.

Reduction in Cost of Maintenance

A cost saving cannot only be attributed because the additional time to complete the unplanned event, but also the unpredictable nature of an unplanned event means that there will either be a backlog of work generated as the planned work is pushed back in favor of the unplanned work, which needs to be cleared by either field service or contractors. In the cases where there are available technicians to fix the breakdown, this would mean the technician would have an efficient utilization and present an opportunity for cost saving.

Increased Production

In the event that the mobile fleet is the bottleneck of production in an operation, then improving the availability will improve the production. It is important to remember that machine availability can only equate to production if it is being utilized.

Spares Inventory Reduction/Optimization

The requirements of the parts are planned for the maintenance activities. They can be ordered effectively and stocked for the minimum time. The high value insurance items can be minimal with reduction in uncertainties in the failures. There is also a relationship between the economic order quantity and the mean time between shutdowns (MTBS).

Reduction in Over Investment

Where the mobile fleet is not the bottleneck, improvements in availability can be attributed to reducing the fleet based around the methodology that less machines can produce more.

A sound strategy does not primarily seek to reduce the maintenance on the equipment. It ensures most of the maintenance tasks are planned rather than unplanned. This can be achieved by leveraging the vast amounts of data from machine maintenance histories, telemetry on the machines and cloud-based lifecycle modeling.

This article was submitted by Sandvik.

Reference

Knights, P.F., Jullian, F., and Jofre, L. “Assessing the Size of the Prize: Developing Business Cases for Maintenance Improvement Projects,” Proc. 2005 Australian Mining Technology Conference, pp. 151-164, Fremantle, Washington, September 27-28, 2005.